Welcome to the last installment in the Summer Gift Series: What is Art For?, where we’ve been asking that question and exploring some answers. (And below, there's a link to a Sense Writing gift sequence that you can lie down with to see what emerges in practice.)

As artists and writers, we want to feel connected to ourselves, our communities, our creative voices.

In the last couple of emails, we’ve talked about this desire— the urge to express ourselves, even in times of crisis, with full, embodied responses, instead of getting stuck in coping mechanisms.

We know how it feels to keep getting stuck— to try again and despair, to cling to normalcy, maybe to try to “rise above it all” and end up disconnected from… “it all.” Including ourselves.

And we also know the feeling of connecting to our deepest urge to create; when we lose ourselves in a project, or when we sit down to write and the words seem to emerge organically. When we get into that state of flow and something just clicks.

And of course, if we know flow, we also know how it feels to lose it— when we don’t know how to get back to it. When it feels like we’re chasing it or circling around it, but still finding ourselves missing it. Probably forever :(

So how do we make it easier to get unstuck? How do we stop chasing and get into the flow?

Just Eat the Mango

When asked to explain the Feldenkrais Method, Moshe Feldenkrais said, "It's like telling somebody what's the taste of a mango. Unless you eat it, you don't know what the taste is." It’s easy to say “just do it” — just sit down and write — and most of us have tried that.

But when we’re talking about learning on a bone-deep neuroplastic level, the kind that we do in Sense Writing, we need a safe container. To learn (or learn again) how to enter an exploratory state of flow, we need to start from the ground up.

In the last blog, we talked about how my professor Rolf Sattler’s pioneering view of botany — one that didn’t separate the scientist from nature itself — helped inspire Sense Writing.

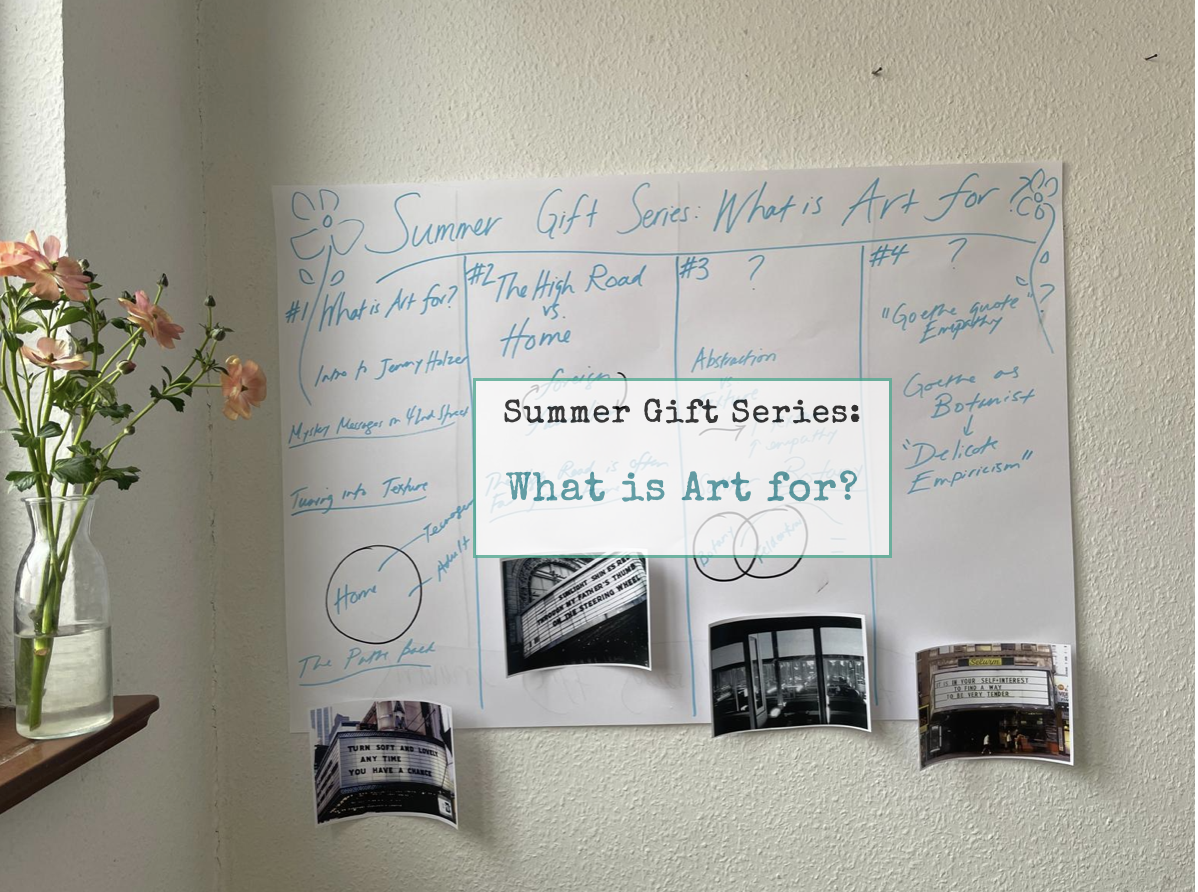

When teaching Sense Writing, I often use botany and gardening metaphors, which can be deeply accurate in their ability to convey both the simplicity and complexity of the creative process. And it’s also how the Sense Writing 12-week course is organized.

With the next session of the course coming up, I’m excited to share a peek with you. This is the framework that has supported hundreds of students in showing up for their stories and for the world around them and fostering a resilient creative practice.

It’s how we eat the mango.

These are the 4 parts (along with some images from the course’s animation):

Here, we start to form a relationship with the terrain of our body and external environment. We see that the terrain is there to explore, the spaces we may have been avoiding out of habit or fear, and establish a safe, fertile place from which to work.

Till the soil and soften the terrain, so that the ground becomes not just a refuge but a place from which a story can grow.

As we build awareness of our internal body, our capacity to absorb and process sensation grows— and we begin to connect to language, allowing the stories that are in us to root and surface and gradually see a path to the outside. We get the reassurance that there is something to step into, something waiting for us to discover.

Like the inside of a seed reaching out from its shell toward sunlight, the story sprouts, somehow instinctively knowing it is there.

Just like light, soil, water, and time work together to create a tree, many neuroplastic processes are organically working together in this phase. Without pushing, we encounter our voice and the intrinsic structures of the stories we’re telling.

Just like a tree grows with both steadiness and ease, you’ll get to feel how powerful processes can support your writing without having to push or pull to reach anything.

As you experience the processes we practice and learn how they work, you trust them, and by extension, yourself. Here, in a deep state of learning and creativity, we integrate specific methods to find the connections between stories, strengthening your craft from the inside out.

Held in this environment, you understand that you don’t need to hold on or grab too tightly to develop a resilient writing practice all your own.

I hope you enjoyed this Summer series, What is Art for?

And that you began to get a glimpse of how it feels when you can step into your creative landscape, and develop an interconnected, self-generating artistic awareness that you can access with trust and curiosity.

And if you would like a bone-deep reminder, you can try this Sense Writing sequence out: